Data Collection on Rumble

A video-hub for fringe discourse

In recent years, Rumble has emerged as one of the central audiovisual platforms within alternative media ecosystems (Balci et al., 2024). Initially founded in 2013 as a video-sharing site in Canada with a focus on free speech, Rumble surged in popularity beyond its core audience (mainly from the U.S.) around 2020, capitalizing on growing distrust toward mainstream social media platforms like YouTube, Facebook, or X (Shaughnessy et al., 2024).

Today, Rumble functions as a central discourse space for the MAGA (Make America Great Again) community, positioning itself as a champion of "uncensored" content, creating a fertile ground for extremist, conspiracist, and other fringe communities. Users who were deplatformed from larger sites often find a new home on Rumble, enabling the platform to become an essential node in the broader disinformation ecosystem (Balci et al., 2024a; Mell-Taylor, Alex, 2021).

Prominent figures associated with conspiracy theories — ranging from COVID-19 denialism to election fraud narratives — have amassed large followings on Rumble. Content that would be heavily moderated or banned on larger platforms is often allowed to thrive here, posing the challenge for researchers to gain insights into the networks and narratives permeating the online space (Balci et al., 2024b; Thompson, 2024).

The challenges of website architectures

Rumble is a good example for the heterogenous landscape of website architectures. Much of the relevant information is loaded dynamically via JavaScript, depending on specific trigger actions on the website, like the user clicking a button or scrolling something into view. This is where traditional solutions like “Beautiful Soup” in the Python world or “rvest” in the R world fall short, as they can’t fetch dynamically generated content.

Selenium is an open-source software framework widely used for automating web browsers. Originally designed for testing web applications, Selenium has become an essential tool for researchers, especially those involved in web scraping and data collection from online platforms.

At its core, Selenium allows a user to programmatically control a browser like Chrome just as a user would: clicking buttons, filling out forms, scrolling pages, and downloading content. This ability makes it invaluable for collecting data from dynamic websites that rely heavily on JavaScript and interactive elements, which traditional scraping methods often struggle to handle.

Ethical considerations

Crucially, among all types of data collection, webscraping is the most intricate with legal as well as ethical consideration constantly evolving through legislation such as the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or the Digital Services Act (DSA). Responsible scraping practices should always include data minimisation, anonymisation, and a clear purpose aligned with public interest or research. Be sure to always check the platform’s or website’s Terms of Service and look for structured alternatives such as APIs. See also the chapter on the current state of webscraping on the hub.

Note

While Selenium offers considerable advantages regarding is adaptability, data collection with it is often resource-heavy with long compute and waiting times. Depending on your project and its demands, consider alternatives like those mentioned above. You can find great tutorials on puppeteer and rvest on the hub. Be sure, however, to check out the programming language they use. If limited to Python, the main alternative to Selenium is Beautiful Soup — a Python library for extracting data from HTML and XML sources.

What you will learn in this chapter:

This chapter teaches you how to use Selenium for webscraping, including:

- Basic setup of a WebDriver instance;

- Core functions to find, fetch and interact with web elements;

- Collection of video information from Rumble.

It will walk through central areas of the video platform – the trending page, search queries and video pages.

Along with this tutorial, a custom Python package was developed to help you collect more complex data from Rumble. More information about its capabilities is provided at the end.

For this tutorial it is best to follow along using a Jupyter Notebook either in your browser or any common programming environments (IDEs) like (Peters, 2022).

Basic Setup

We will first install the selenium package, as well as other packages needed later, via pip.

!pip install selenium requests

#The exclamation point is used to signal to your machine that this shell command (“pip install something”) should be run externally

From the selenium package, we will import the WebDriver module and launch a web browser instance of Chrome. With the driver object, you can now control the browser. We use the get() function to navigate to the Rumble homepage.

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

# Launch the browser (Chrome in this example)

driver = webdriver.Chrome()

# Navigate to Rumble's homepage

driver.get("https://rumble.com")

Note

While the selenium package should automatically download the necessary browser drivers such as geckodriver for using Firefox or the chromedriver, it is possible that your browser version is not compatible with any of those. If you want to use chrome, check your browser version and visit the chrome-for-testing dashboard to download the corresponding driver for the platform (OS) of your computer. You can the point to the newly downloaded driver file with the Selenium Service module.

CHROME_DRIVER_PATH = "PATH TO YOUR DRIVER FILE"

# initialize the Service module and pass the path to the executable (the chromedriver file)

custom_driver_path = Service(CHROME_DRIVER_PATH)

# create a new instance of the Chrome driver with the specified path

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=custom_driver_path)

# Navigate to Rumble's homepage

driver.get("https://rumble.com")

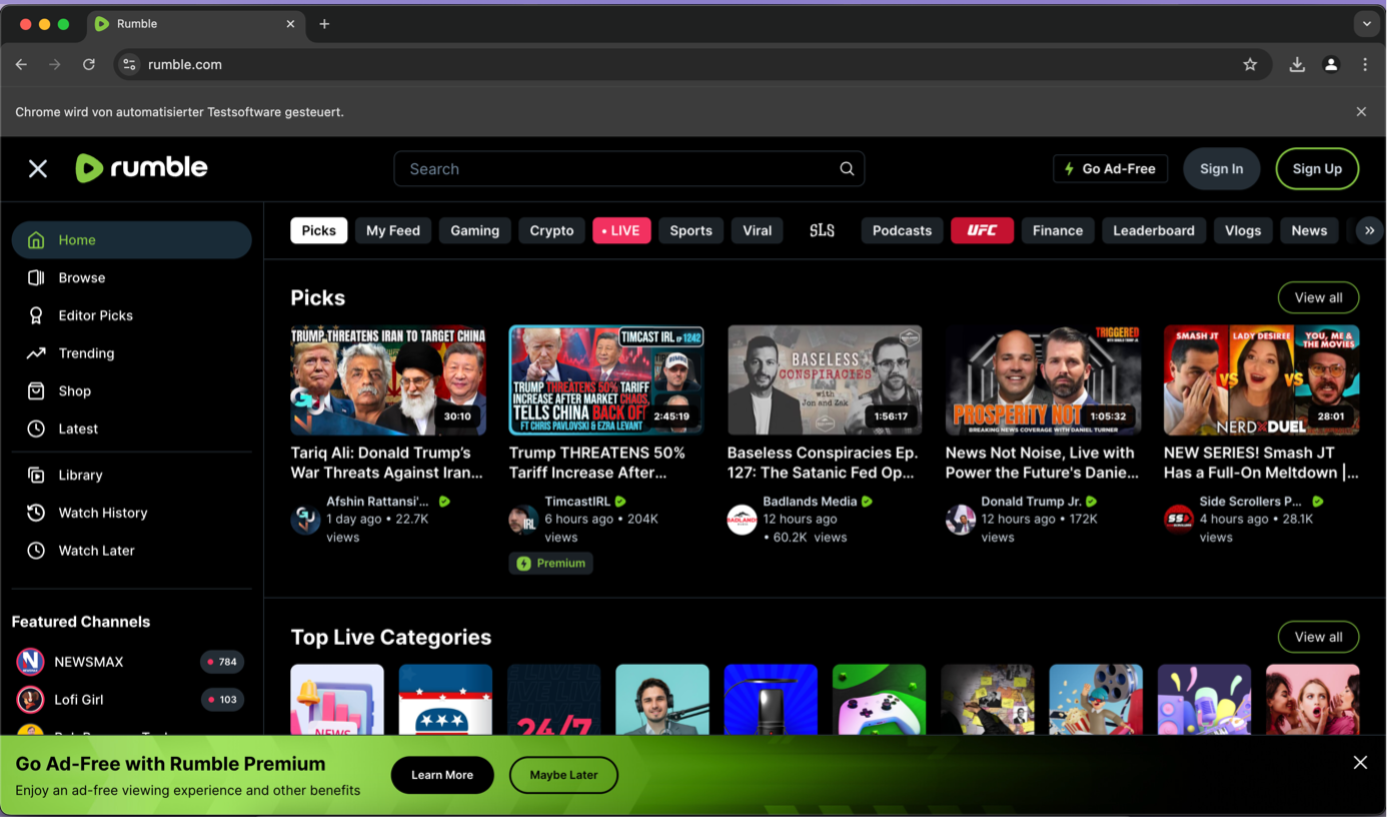

Screenshot of Rumble’s landing page with automation disclaimer at the top

Hint

At the top of the browser window, it reads “Chrome wird von automatisierter Testsoftware gesteuert” – This disclaimer signifies that your browser is controlled by Selenium. At the same time, this kind of information is also passed to the website servers, whenever you make a request. Some pages explicitly prohibit the usage of automated browser clients to visit their pages and have put in place different blockers and CAPTCHA forms. Reacting to this, more advanced instances of the Selenium WebDriver have been developed. For an introduction to the “undetected chromedriver” click here.

Interacting with elements on a webpage

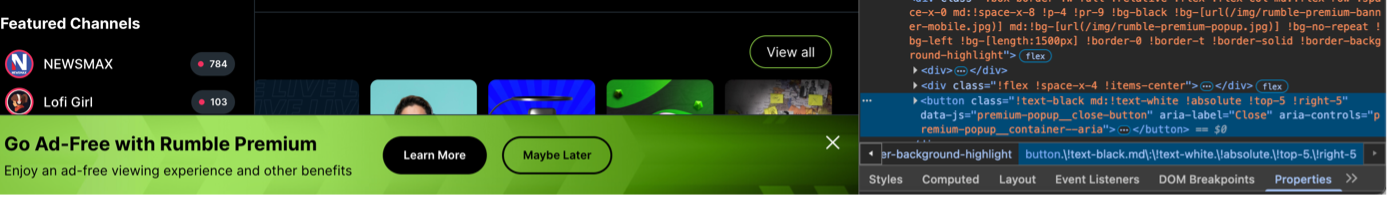

Before heading to the breadth of extremist content on Rumble, the following ad appears at the bottom of the page. While we could simply close it manually, this presents a great opportunity to learn the core concept of data collection with Selenium – It’s all about the elements.

Screenshot of Rumble’s ad popup page and the associated DOM element

Understanding Web Elements and the DOM

When a web browser loads a web page, it reads the HTML (HyperText Markup Language) and constructs a representation of the page in memory called the Document Object Model (DOM). The DOM is essentially a tree-like structure where each piece of HTML —such as <div>,<a>, <p>, or <img>— is represented as an object or node in that tree. Selenium lets us find data on the page by explicitly pointing to a web element. More information about how to use the DOM and DevTools can be found here.

Instead of manually clicking the “X” button, we find the corresponding element in the DOM, so we can point to it and let the WebDriver close it for us. We will use the find_element() function. Every web element has certain properties and attributes. Similarly, there are multiple viable ways to point to an element. Among them, css selectors and XPath are the most prominent ones, striking a good balance between ease of use and explicitness. In this tutorial, we will focus on an element’s XPath to find and interact with it.

Note

If you want to explore the usage of CSS selectors for Selenium, you can find great resources here.

XPath uses path-like syntax. Upon inspecting the button “X” element, we find its node name to be “button”. However, for this ad pop up alone, there are three button nodes. So, we look for more unique attributes, like classes, id’s or aria-labels. Much like a file path on your computer, the longer the path, the more specific the kind of object it is pointing to. In this case, the element has an associated aria-label value “Close” we can use to find the element, store it in an object and use the click() function to trigger a mouse click action.

from selenium.webdriver.common.by import By

#Most common XPath syntax: ‚//<nodename>[@<attribute>=“value“]‘

# Find the "X" button and store it as a webdriver element

close_button = driver.find_element(By.XPATH, '//button[@aria-label="Close"]')

print(close_button)

This output shows how Selenium stores a web element:

<selenium.webdriver.remote.webelement.WebElement (session="cb1235bf141111e2957a342a38a68670", element="f.CF46E617C588DFF5C8E2BDB69B5DF780.d.6FFCA08F353769BE84D96D5E08180AC4.e.23623")>

Now we can click this button and see the pop-up being closed.

# Click the "X" button to close the pop-up

close_button.click()

Rumble's trending page

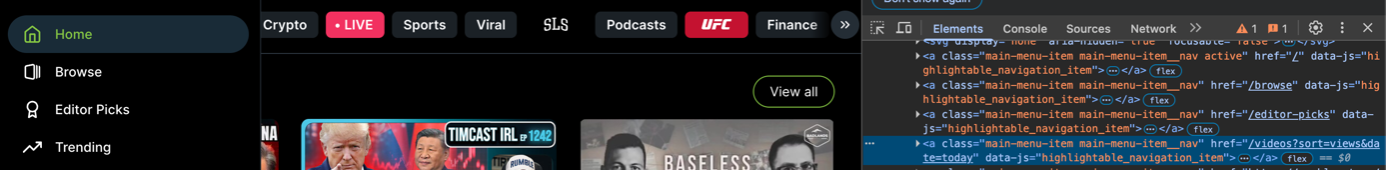

Rumble’s trending page is a good seismograph of the latest MAGA and extremist discourses in the US. After inspecting the menu bar on the left, you can see that the different sections are not represented as button elements but rather as hyperlinks with which we can navigate to the respective subdomain. Still, we could find and store the element through the href attribute and click it, like any user would do on the website. Alternatively, you can navigate to the subdomain directly via the get() function.

Note

There is no general rule as to either click on hyperlink elements or load the page directly. However, the get() function will load the whole page, whereas sometimes click actions on dynamic webpages will only reload a certain part of that page. This is important for large-scale data collection with time constrains but can be neglected within the scope of this tutorial.

Screenshot of Rumble�’s menu bar with <a> elements displaying the subdomains

# Find the "Trending" link and store it as a webdriver element, then click it

trending_page = driver.find_element(By.XPATH, '//a[@href="/videos?sort=views&date=today"]')

trending_page.click()

#Alternatively, you can use the subdomain directly to navigate to it

driver.get("https://rumble.com/videos?sort=views&date=today")

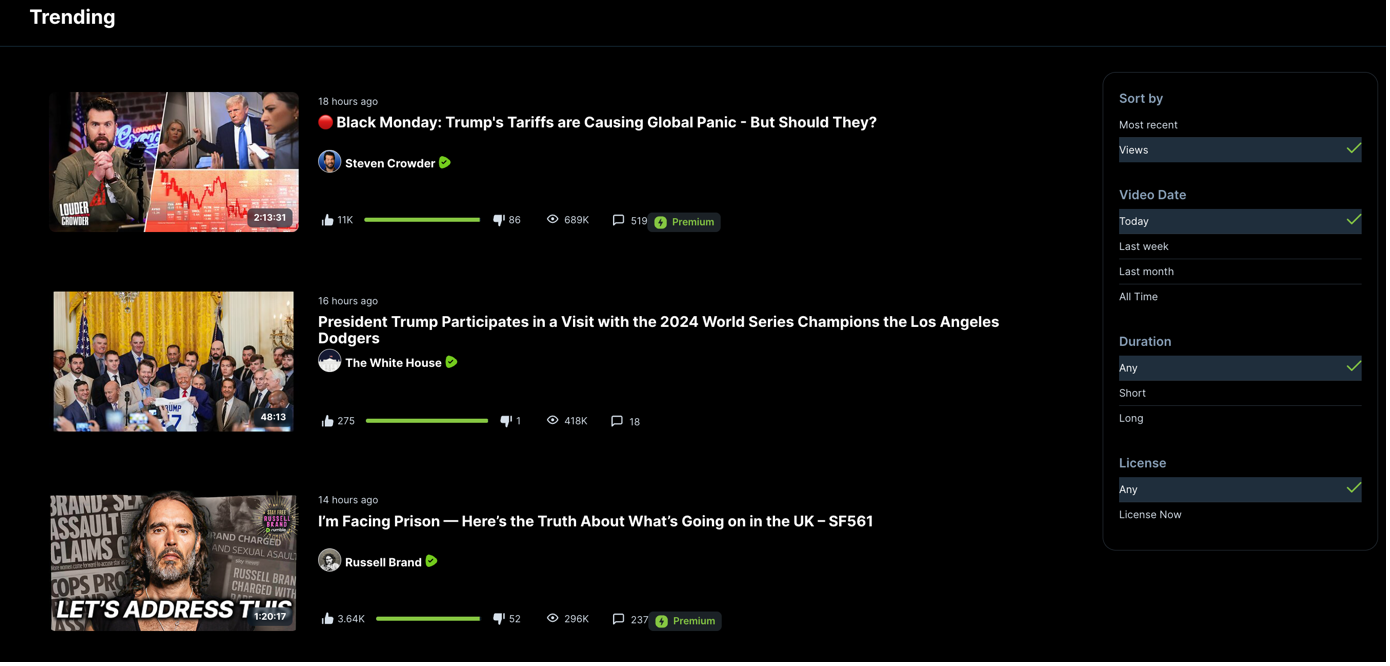

By default, the trending page lists the most viewed videos of the day. On the right side, there are many different filter options to choose from. Instead of today, we want to inspect the most viewed videos of the past week. Again, we could find the filter option as an element and click it, or we slightly change our URL to directly navigate to that filtered page.

Screenshot of Rumble’s trending page with filter options

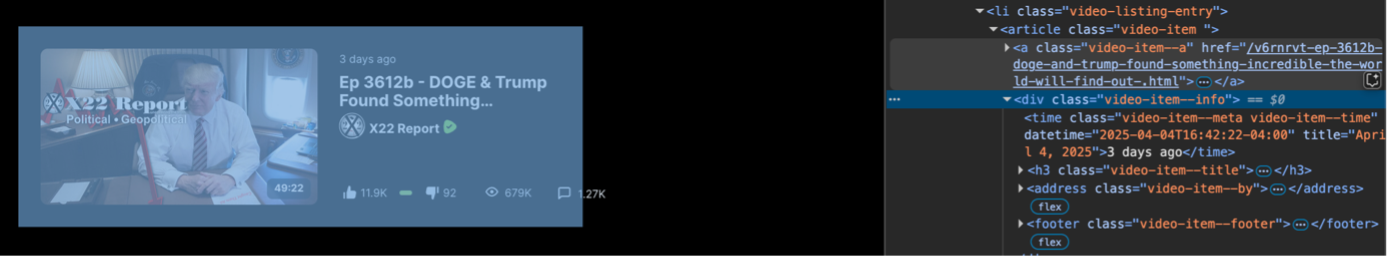

Looking at the video elements in the DOM, we can see clearly structured <li> items with the class “video-listing-entry”, which hold different child elements and attributes. On Rumble, there is no infinite scroll, as the content is separated into different pages. Each page contains 25 video items.

Screenshot of a video item with its associated DOM element

We can identify and store these video items by utilising the find_elements() function. While there are already valuable data points visible from the listing view alone, we don’t have access yet to the video description, its caption and the comment section. Therefore, we will only fetch the ‘href’ of each video and later visit each video page retrieve all data in detail.

Doing so, we write a small function that not only finds the elements but also extracts their values for the ‘href’ attribute. This can be easily done with the get_attribute() function.

def collect_video_links(driver):

#Define an empty list to store the video links

collected_links = []

#Find all video elements that contain the video links

links = driver.find_elements(By.XPATH, "//a[@class = 'video-item--a']")

#For each link, get the href attribute and add it to the list

for link in links:

href = link.get_attribute("href")

if href not in collected_links:

collected_links.append(href)

return collected_links

video_links = collect_video_links(driver)

print(video_links[:3])

['https://rumble.com/v6ri2ut--01-04-2025-makeleio.gr.html', 'https://rumble.com/v6rjszf--why-the-medias-bombshell-deportation-story-is-one-big-lie.html', 'https://rumble.com/v6ro0xt-stock-market-bloodbath-after-china-places-34-tariff-on-us-trump-holds-firm-.html']```

If we want to retrieve the video items for multiple pages, we can do so by utilising keyboard actions to simulate user behaviour like scrolling. At the bottom of the trending page, there are page elements we can scroll to and click. Ultimately, we want to create a loop that goes through the pages and stores the video links. There are again multiple viable ways to do this, either specifying the number of pages we want to retrieve data from or the number of videos we want to retrieve. In this case, we loop over the pages until we reach the number of videos links that have been defined. We want to fetch the 50 most viewed videos of the last week.

In prior versions of the Selenium python package, many user actions like scrolling were performed by letting the WebDriver execute some lines of JavaScript code. Now, most common actions are nicely wrapped and easily executable through Python directly. Here, we need the “ActionsChains” classes and utilise the scroll_to_element().

from selenium.webdriver.common.action_chains import ActionChains

def collect_multiple_pages(driver,limit:int=50):

video_links = []

# Iterate over as many pages as needed to fetch the desired number of video links

while len(video_links) < limit:

# Scroll to the "Next" button to ensure it's in view

button = driver.find_element(By.XPATH,"//li[@class='paginator--li paginator--li--next']")

ActionChains(driver)\

.scroll_to_element(button)\

.perform()

# Use the collect_video_links function to get video links from the current page

page_video_links = collect_video_links(driver)

# Add the new video links to the list

video_links.extend(page_video_links)

button.click()

return video_links

video_items = collect_multiple_pages(driver,limit=50)

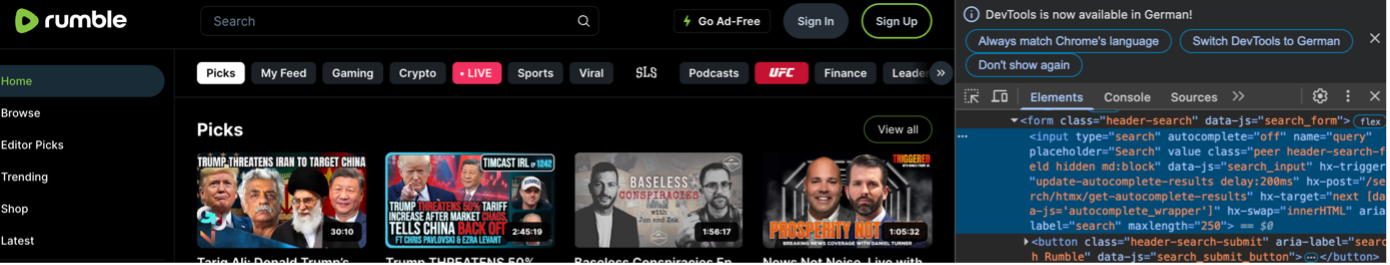

Automate search queries

Before turning to the detailed video data, we introduce one last core method for interacting with web pages via Selenium – sending keys or input. Whenever we have an input element like a search bar or a form to fill out, we can send user input automatically and thus automate a variety of processes. In this case, we want to utilise the search bar, insert a search query, and simulate a key press “ENTER” to automate the search on Rumble.

Screenshot of Rumble’s search bar with its associated DOM element

from selenium.webdriver.common.keys import Keys

def search_query(driver,query:str):

# Find the search input by its attribute

search_bar = driver.find_element(By.XPATH, '//input[@type="search"]')

# Send your query

search_bar.send_keys(query)

# press Enter to submit the search

search_bar.send_keys(Keys.ENTER)

# Our search query is "trump tarrifs"

search_query(driver,"trump tarrifs")

By default, the resulting page will show the most relevant results based on your query. The same filter options we have introduced on the trending page apply here. You can now use the collect_multiple_pages() function to iterate over the result pages and collect the video links.

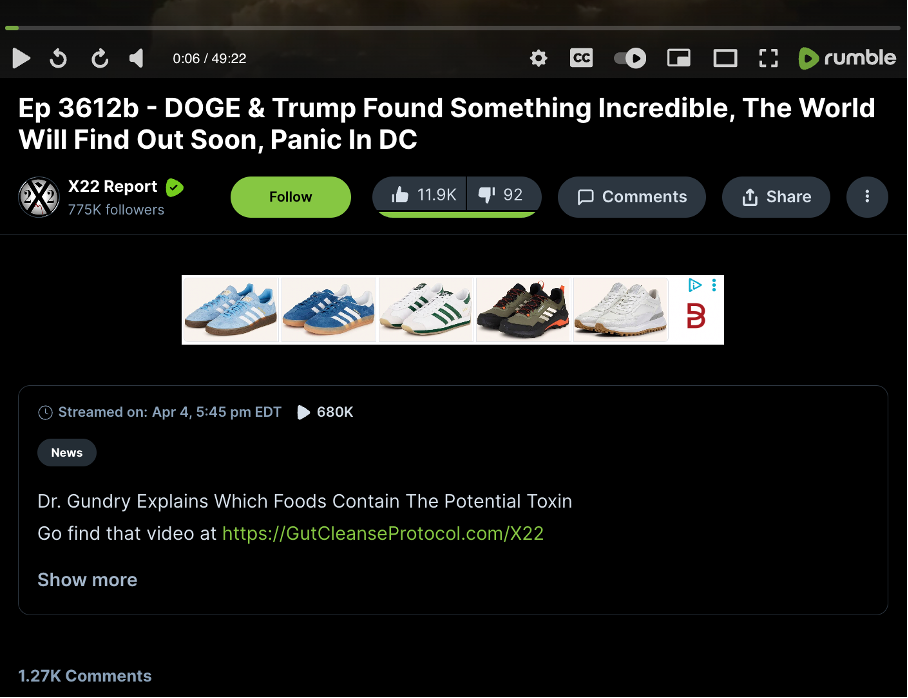

Collect video information

After we have collected video links from the trending page or through our search query, we can now inspect a single video page for relevant data points.

_Screenshot of a single video page with relevant metrics and data points _

For every video, Rumble provides a breadth of information we can collect. However, unlike datapoints such as the title or the author channel, much of the information is presented in a user-friendly way unfit for analyses. For instance, the view count is not a classic integer but abbreviated with a capital K to signify 680,000 views – so are the likes and dislikes for that video. Even after inspection of the DOM, one realises that we need to convert this data to make it usable for analysis.

We can create a function that fetches the view count and – depending on the letter – converts it to its associated integer value.

def collect_view_count(driver):

#Find the view count element using its XPath

view_count = driver.find_element(By.XPATH, '//div[@class="media-description-info-views"]').get_attribute('outerText')

# If the value is above 1,000 it will be converted to "1K". So we can identify the k in the string.

if "K" in view_count:

converted_video_count = int(float(view_count.split('K')[0]) * 1000)

# If the value is above 1,000,000 it will be converted to "1M". So we can identify the M in the string.

elif "M" in view_count:

converted_video_count = int(float(view_count.split('M')[0]) * 1000000)

# Any value below that is displayed as a classic integer and can be converted directly.

else:

converted_video_count = int(view_count)

return converted_video_count

single_video_view_count = collect_view_count(driver)

print(single_video_view_count)

680000

Even after retrieving all visible data from the video page, there is limited insight into the video’s content, especially if it’s an hour-long stream. Luckily, Rumble provides captions we can fetch and store as text for content analyses. We will create a function that finds the element and makes a request with the help of the ‘requests’ Python package. It then encodes the response as text if successful or prints out the error message.

import requests

def retrieve_captions(driver):

# Find the captions track element and store the src attribute

src_path = driver.find_element(By.XPATH, '//track[@kind="captions"]').get_attribute('src')

# Utilize the requests library to fetch the captions file

caption_response = requests.get(src_path)

# Check if the request was successful (status code 200)

if caption_response.status_code == 200:

return caption_response.text

else:

print(f"Error: {caption_response.status_code}")

return None

captions = retrieve_captions(driver)

print(captions[:90])

WEBVTT

00:00:47.340 --> 00:00:49.340

Welcome, you're listening to the X-22 Report.

With the core methods shown in this tutorial, you are now able to navigate to Rumble or any other website (static or dynamic) with an automated browser and retrieve or interact with its web elements. Beyond this, you can expand the code to fetch more data points from the video page and automatically navigate through the different domains of interest on Rumble. Once your code is ready, you can switch to Python scripts and run them daily for monitoring purposes.

Advanced usage

The platform’s web page structure is complex, with many metrics and elements posing challenges for data collection. For instance, metrics like the date format depend on the content being a video or a live stream. The display of the description text depends on its length. Rumble channels can also limit the availability of their video’s comment section to logged-in users.

Therefore, we at polisphere have created an open-source Python package called “rumble-scraper” to help you with Rumble’s complexity and data collection obstacles. It includes the capabilities to

- Collect videos with all filter options from the trending and browse page

- Collect all visible data points from video pages, including video description and the comment section

- Log-in with user credentials

References

-

Balci, U., Patel, J., Balci, B., & Blackburn, J. (2024a). iDRAMA-rumble-2024: A Dataset of Podcasts from Rumble Spanning 2020 to 2022. Workshop Proceedings of the 18th International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media.

-

Balci, U., Patel, J., Balci, B., & Blackburn, J. (2024b). Podcast Outcasts: Understanding Rumble’s Podcast Dynamics. arXiv Preprint arXiv:2406.14460.

-

Mell-Taylor, Alex. (2021). Rumble Is Still Where the Right Goes to Play. Medium. Retrieved April 09, 2025, from https://aninjusticemag.com/rumble-is-still-where-the-right-goes-to-play-d3fe7df98875.

-

Shaughnessy, B., DuBosar, E., Hutchens, M. J., & Mann, I. (2024). An attack on free speech? Examining content moderation, (de-), and (re-) platforming on American right-wing alternative social media. New Media & Society, 14614448241228850. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448241228850.

-

Thompson, S. (2024). I Traded My News Apps for Rumble, the Right-Wing YouTube. Here’s What I Saw. The New York Times. Retrieved April 09, 2025, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/12/13/business/rumble-trump-bongino-kirk.html.